Peter Piller is an artist whose practice centers on the collection and recontextualization of found images, particularly from newspapers and archives. By isolating and classifying photographs, Piller reveals how everyday images construct meaning through repetition rather than singularity. Light in his work is not treated as a dramatic or expressive element but as a functional, often overlooked condition—daylight, flash, or glare that quietly structures the image. In his work, Piller exposes the neutrality and absurdity embedded in documentary photography, prompting viewers to reconsider how visual information is produced, ordered, and perceived.

THE LIGHT OBSERVER : As an artist, you’ve spent years exploring the relationship between photography, archives, and the ways historical images are revisited. How did your interest in archives and found photography first develop, and what draws you to this method of working?

PETER PILLER : My engagement with archives began during my studies in the 1990s, when I worked in the archive of a media agency. My task was to sift through regional newspapers, which inspired me to collect and categorize thousands of press photos. Over time, through recommendations and sometimes by chance, I gained access to other archives, acquiring vast quantities of images and, in recent years, increasingly visiting specialized university libraries. A flood of images does not overwhelm me; rather, I find joy in sorting through large volumes, revisiting them, and discovering overlooked details. I am drawn to placing images in new contexts, detached from their original meanings.

Your series Geröll focuses on traces left by landscapes—shapes and forms that hint at geological processes and human intervention. What inspired this project, and how do you perceive the relationship between landscapes and memory? Additionally, you’ve included your own images and drawings in the project. What motivated you to incorporate your personal work, and how do these elements contribute to the overall narrative?

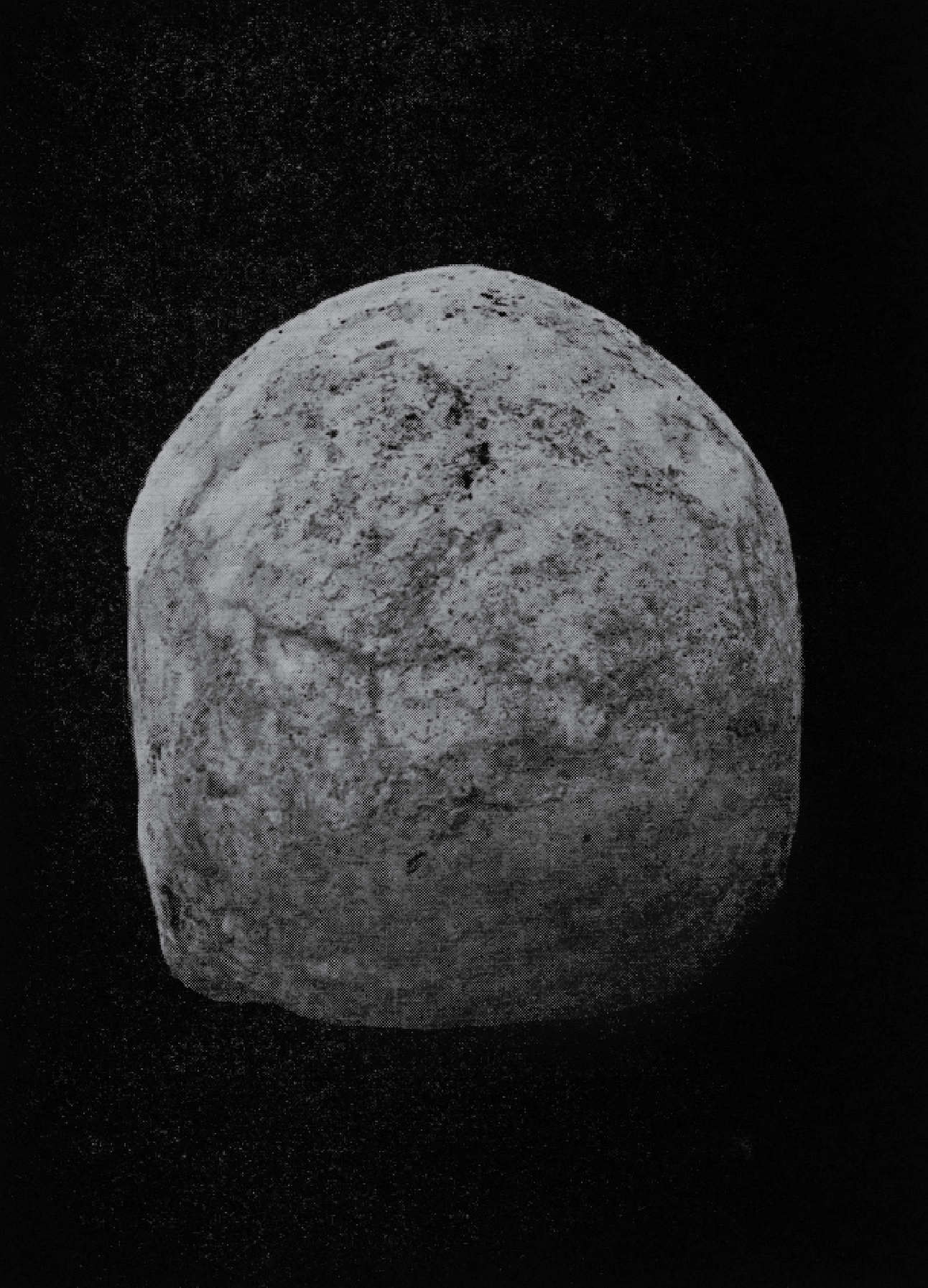

Geröll is not primarily about landscape; its roots lie in my years of intensive study of prehistoric art. I have visited numerous caves in southern Europe, explored museums and specialist libraries, and engaged deeply with the subject through extensive reading. Essentially, I followed a fascination—a light. The beauty, mystery, and contemporary relevance of prehistoric art, along with the many questions it raises about human culture during the Ice Ages, captivated me. These images, paintings, drawings, and illustrations from my research became a constant presence in my everyday life, influencing how I perceive and photograph the world. It felt natural to place the photos I found in these books alongside my own images and drawings. The narrative is associative—connections remain fragile. Instead of providing definitive answers, the work suggests, assumes, and speculates. My photographs include landscapes but also found images that resemble landscapes, like these microscopic views of bone cross-sections. Our concept of landscape is shaped by human intervention. In animistic cultures, however, all beings and things possess animacy, meaning humans are not separate from nature. When you view a landscape from this perspective, you inevitably see yourself reflected in it.

Do you believe landscapes, like photographs, can hold collective memory?

Absolutely. However, landscapes offer layers of time and the possibility of excavation in ways that photography typically does not. Just as collective memory exists, so too does collective amnesia—the inability to “read” images due to a lack of time, patience, or contextual knowledge. With the rise of social media, these conditions for meaningful image interpretation are increasingly undermined. Landscapes also reveal societal tensions and priorities. For instance, the most intact protected areas are often military training zones, and rare species thrive undisturbed on the manicured grounds of private golf courses.

Your project Afghanistan Field Research is built on archival imagery of a landscape shaped by conflict. How did you approach these images emotionally and intellectually, and what were you hoping to reveal by revisiting and reordering these visual documents?

Afghanistan Field Research consists of nine images sourced from a botanical publication. Eight of these depict flowers growing from rocky ground, while the central image shows an open hand presenting blackberries in close-up. When I combine images, decide on sizes, paper, framing, arrangement, or titles, these choices serve as my commentary and intellectual reflection. Yet, once the work is complete, it is no longer about me. What matters is how the work engages the viewer and the responses it provokes.

The title of your series Immer noch Sturm (Still Storming) suggests an ongoing presence of the past. This project also uses black-and-white photography, where light and contrast play a crucial narrative role. How did the interplay between light and landscape guide your work on this project?

In Immer noch Sturm, I juxtapose found photographs of World War I battlefields with images of sea surfaces from a nautical textbook. I searched extensively through libraries to find landscape images that convey the devastation of war without showing soldiers or weaponry. The war has inscribed itself in these landscapes, just as the storm shapes the sea—and the storm continues.

Your work often possesses a quiet, meditative quality, where light functions as a narrative element. Do you consider light to be a subject in itself, or more of a tool for shaping meaning?

I spend considerable time with my materials. While I wouldn’t describe my process as meditation, it may resemble it in that I work until I become thoroughly familiar with the images. Once I reach the point of boredom, I know I am ready to proceed. Photographers have a unique sensitivity to light—whether it’s a surprising illumination or the neutrality of diffuse light. Yet for me, light is less about seeing and more about feeling. Following a light in the dark, perceiving a glow—it is an impulse, not a plan. Light not only falls on objects but also penetrates them. For me, light functions as both an image and an answer to the question: Why make art at all?

In your work, landscapes are never just visual backdrops—they carry histories, politics, and memories. How do you see the artist’s role in uncovering these latent narratives?

The artist’s first responsibility is always to himself/herself. The way I move through the world—the books I read, the films I watch, the art I admire, and my ongoing efforts to stay curious—shapes my work more than any calculated intention. I strive to present landscape as the visible sum of many decisions. My work offers suggestions rather than conclusions and allows for misunderstanding and ambiguity. Many of my pieces risk being deliberately overlooked. I create for the second and third glance—the first impression is less important to me.

You have spoken about the idea that images “speak” when placed in relation to each other. How do you approach the act of sequencing and curating your findings?

Understanding how images communicate with each other has become central to my practice. Each image, like each word, carries multiple meanings. When images are placed together, new and unexpected meanings emerge. My process involves listening, experimenting, and allowing these interactions to unfold. Images do not merely illustrate concepts; they reveal more than can be explicitly stated through their size, materiality, and context.

How do you decide when a project is complete? Is there a point when the images stop revealing new connections, or does the process remain open-ended?

I have always found closure through making books—I have created more than forty to date. This process helps me focus my final energies and then let go. Completing a project is essential for me to move on to new work. However, I occasionally reuse images across different projects. In that sense, true completion remains an aspiration rather than a reality. The longer I engage with a subject, the more connections continue to emerge.

Has your perception of light—whether natural or metaphorical—evolved throughout your career? How does it manifest in your most recent work?

Over time, light as a metaphor has become increasingly significant to me. As a younger artist, I felt a stronger need to impose systems of order, even when they were more obstinate than functional. In recent years, I work more intuitively—the light strikes and brings warmth.

What are you currently working on, and are there new directions or ideas you are exploring regarding landscape, light, or the photographic archive?

I recently completed a substantial body of work with Geröll and am trying to resist further immersion in prehistoric art. Instead, I take long daily walks, photograph, visit libraries, draw, and wait. Waiting has always been part of my process. For now, I cannot articulate exactly what I am working on—and even if I could, I would prefer not to. I will share more when the next exhibition is ready. Everything I need is close by.