Thélonious Goupil is a French industrial designer, who sees design as a way to explore and experiment — rooted in everyday needs, he reflects on the life of his objects as much as their production, finding sustainable solutions with a focus on thoughtful making. Through his projects, he develops a rather unique formal language.

THE LIGHT OBSERVER : You’ve been studying Product Design in Paris. After these studies, would you say you had a defined idea of what you wanted to do as a designer, or is it something that came with time and opportunities?

THELONIOUS GOUPIL : Somehow, yes. During my studies, I already wanted to be a design generalist and work on different projects and scales: from space to exhibitions, as well as product, graphic design, research, and books. This variety of approaches and projects felt very enriching to me. That’s why I initiated Collections Typologie with some friends so I could work on books and exhibitions. I’m lucky this project led me to meet many people, and slowly I started being offered different kinds of projects.

What fuels your practice? What are the things that stimulate you, that you feel influence your work?

Traveling, whether abroad or even just to the countryside, is always a good way for me to feel stimulated. I’m always on a quest for the ingenious, resourceful solutions people find to repair or improve things. There’s something very spontaneous and inspiring in those solutions. They are a testament to the care people have for the things that surround them, which moves me deeply. It carries something almost spiritual—this extra attention makes it more than just a simple object. One of my most unforgettable trips was to Nepal for this reason. There, the relationship to objects is the opposite of the common neglect with which we treat things here, where everything is replaceable. I think I aim to design objects like people repair and improve their things, as spontaneously as possible, with the right solution for a given context.

How important is drawing and prototyping in your practice?

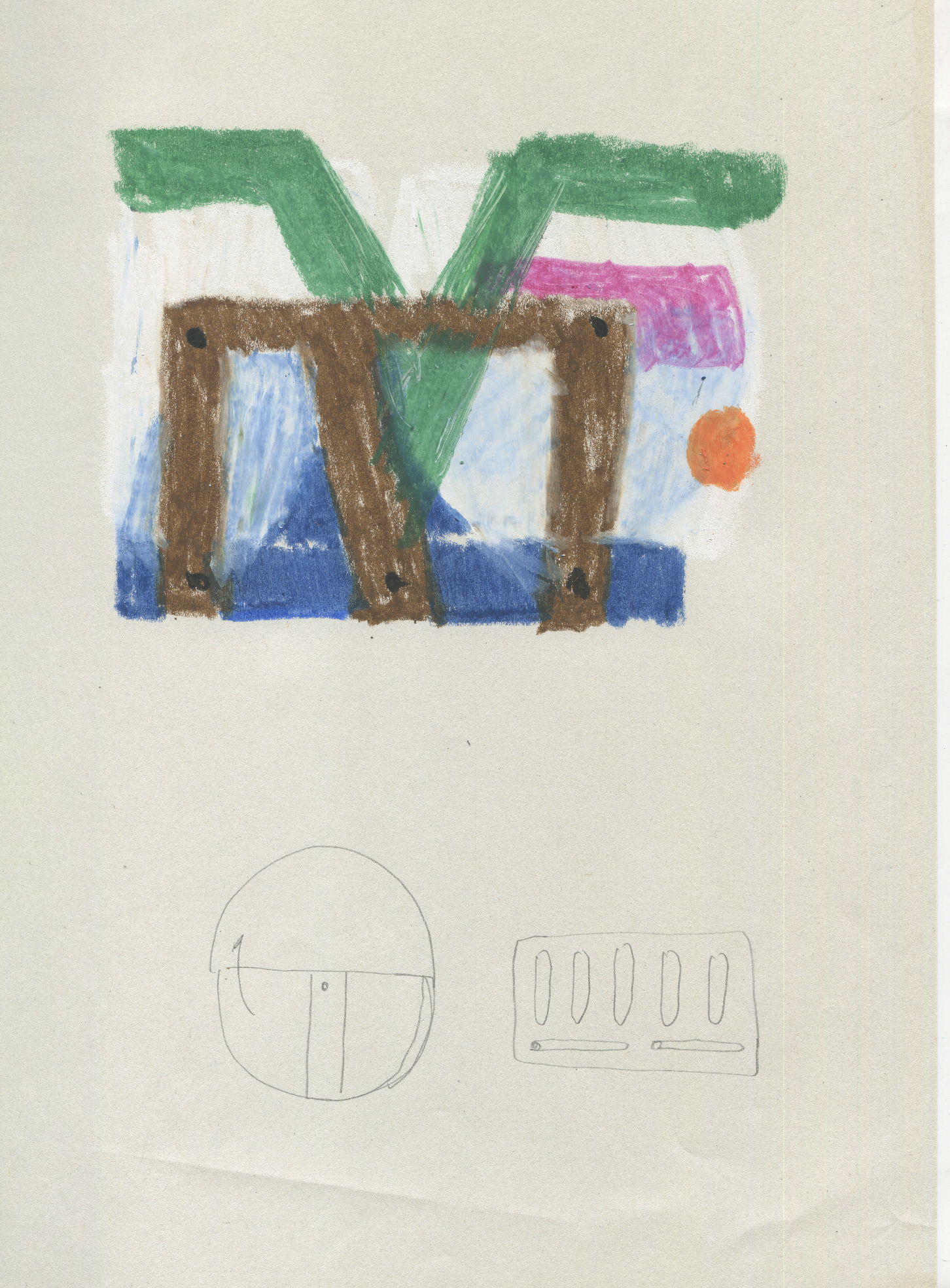

I try to stay as far from my computer as possible during the creative process. This means I rely heavily on my hands to seek out shapes, ideas, and principles. I’m still trying to find the right method, but my process is a back-and-forth between modeling, sculpting, cutting out, sketching, and then stepping back to reflect on all of that. Nothing good comes up when I think too much, so I believe I should just let my hands find their way. It’s funny because they’re pretty independent—sometimes they make things that are beautiful, but that my conventional designer’s mind isn’t at ease with. That’s when the discussion starts.

In the creative and ideation phase, would you say that experimentation plays a crucial role in the success of a design concept?

Yes, it seems essential, at least at this stage of my practice. I’d describe it as more of a process of confrontation than pure experimentation. Confronting materials and their reactions, shapes and their effects in space, and confronting ideas and models with others. I don’t know if that makes a design concept successful, but at least that’s how I find a design concept.

When working for industrial companies, you must follow some guidelines and deal with constraints. Is there still room for experimentation when you work for such companies?

In my experience, there is still room for experimentation, but it’s more limited, and the rules are just different. In this context, you experiment with the available industrial techniques and tools to make an object that is coherent. It’s more about small solutions, interlocking, and detailing. To me, it feels more technical and less expressive, but it’s a valuable skill that I’m still learning. Of course, it also depends on the manufacturer and the project. For example, I was recently asked to design an object that should be “sculptural.” I’m still working on it, but this shows that sometimes there is a sort of freedom to explore, even in this field.

You also develop smaller projects for associations, charities, and on-site furniture. Do all these projects go through a similar research phase?

Site-specific projects are very different for me. They start with a long observation of the place. I have to be there and physically feel it. Once I have a good sense of the space, the ideas I’m looking for slowly start to show. Since the object is not meant to be replicated in series, I feel less pressure to make something perfect. It’s easier and very pleasant to do.

Observation must also be at the root of your practice, as it is for many people in creative work—that moment when we carefully examine our surroundings to draw out reflections and ideas. Have you come to know what attracts you and what you are trying to recreate or find through your own work?

There is a very strong dominant aesthetic in design nowadays, which is hard to step away from. I think one of my interests is to try to break or at least question this conventional perception of beauty. It’s not something I can pursue in all my projects, but I’m mainly interested in developing designs that make sense within a given context. My work is also a way for me to ask myself questions. For example, what is my role as a designer in this general context of climate change and crisis? What do we need in this situation? If industry is no longer a viable way for designers to make a living, what economy should I invent instead? Is self-production a solution? If so, what kinds of objects might emerge?

It’s common to think that experience leads to a better understanding of things, yet in a creative field, experience isn’t always the key. I find this quote from Achille Castiglioni very true: “Experience does not give certainty or security. On the contrary, it increases the possibility of error. The more time passes, the more difficult it becomes to plan better. The antidote? Start afresh each time, with humility and patience.” We could say he advises experimentation over experience. Is that something that resonates with you?

I strongly agree with the need to be spontaneous, fresh, humble, and patient, even if it’s hard! However, while experience isn’t a synonym for “recipe,” I think it can be helpful in avoiding making the same mistake twice.

You’ve been working on a collection of lamps this year for Small Small Space in Milan. Can you tell us more about the genesis of this project?

SSP is a window shop run by Michele Foti and Layhul Jang in the historic core of Milan. It’s 5 meters wide and 2 meters high, located in a public passageway. They invite all kinds of creative people—artists, designers, architects, or photographers—to exhibit in this space for two weeks. I’ve been enjoying designing lamps recently, so when they invited me, we agreed to present a series of lights. The narrow space led me to design a very flat object to be viewed frontally. My goal was to make the lights myself while achieving a satisfying degree of quality. That’s how I developed this concept of assembling paper and laser-cut, bent steel sheets together with eyelets. This context allowed for a lot of freedom, with no compromises to be made, so I took it as an opportunity to play with shapes and create an expressive series.

In the history of design, lamps are often iconic objects. How do you start working on a lamp? What matters most to you?

There are so many ways to approach it, but in this context, I thought about the light as a decorative object. Not necessarily something to light up a room, but more like a small luminous composition. In an industrial context, I could imagine a lamp I would like to have at home, made with all the details and quality that industrial production allows. It depends on the project.

There’s a heightened sensitivity to light that changes how we perceive our environment. Does that imply a specific approach as a designer?

Indeed, light has a significant impact on how we perceive our environment and, moreover, how we feel in it. Is it cold, impersonal, warm, welcoming, cozy, or too bright? It seems to me that beyond the choice of the bulb, the atmosphere a light creates depends a lot on the material of the diffuser and how it is shaped. This is the difficult part of designing a light. Plastic diffuses light well, but I prefer to avoid it as much as possible due to the sustainability problems it raises. I like glass, but it’s heavy, which is paradoxical for an object meant to be light. Fabric tends to dim light—it’s more of a filter than a diffuser. For all these reasons, the light I prefer is diffused by paper, specifically the right kind of translucent paper. This is where my process gets tricky because paper is hard to manufacture, and you need to invent specific techniques to produce a long-lasting paper light that makes you forget it’s made from a sheet. So it’s really about using paper in the right way to create an object without needing to develop a whole new process, which most companies wouldn’t be able to afford.

Was the idea of a collection part of the project from the beginning?

It wasn’t the first intention, but the design principle easily allowed for creating variations, so it was a good opportunity to do it!

You often propose a collection of objects. I’m thinking of the series of vases for Vitra or the glass pieces for Iittala. You’re also part of Collections Typologie, a journal that investigates the making and life of everyday objects, proposing a catalog or collection to reflect on those. What attracts you to the idea of a family of objects?

I hadn’t realized it before, but it does come back to experimentation. If design is a way for me to understand the physical potential of a shape or an object, then creating a family is a way to compare and observe many differences at once. I guess a sculptor would rarely make only one sculpture in a series; they need more to understand what they’re searching for.

You also often present your objects surrounded by others, not necessarily ones you have designed. What kind of dialogue are you trying to create?

Photographing objects is a very different step for me. I really love photographing them myself because I discover new points of view that I hadn’t expected. An object is not meant to remain on a white background, so when I surround it with others, the idea is to suggest the environment in which it could fit. I can spend a lot of time creating a decor and then retouching it. It’s like painting—I’m trying to compose colors and shapes in the best way to capture a vision.

I think the idea that the life of objects is not only their relationship with the user—a founding concept in design schools—but also their relationship with the objects around them, is quite poetic and true. This is probably more Eastern than Western thinking. Is this something you think about a lot in your practice?

Yes, I do. But I must admit, I try to temper these thoughts about objects. Thinking too much about the relationship of things to each other can be a bit limiting. Even if beautiful, an interior filled with things and no people is lifeless. The risk of focusing too much on creating the perfect atmosphere is forgetting what exists outside our own house. I want to remember that there are people different from me, who live and consume differently. I want to meet them, and I find it more inspiring to be surprised by accidents or unpredictable interiors than by trying to arrange my things perfectly.